Written by Tracy Letts. Belvoir St Theatre. 9 Nov – 15 Dec, 2024.

Why do we enjoy watching families tear themselves apart on stage? Is it cathartic to hear people say the things we never would? Is it comforting to watch people worse than ourselves? Or is it just because the drama gives us a feast of potentially great acting? Whatever it is, August: Osage County at Belvoir has it in spades – an unsettling, addictive blend of harsh truth and dramatic flair.

The Weston family gather after the disappearance of their father Beverly (John Howard). The three Weston daughters, Ivy (Amy Mathews), Karen (Anna Samson) & Barbara (Tamsin Carroll) return with their own dreams and resentments that boil over in the oppressive Oklahoma heat. They are joined by their Aunt Mattie Fae (Helen Thomson), her husband, Charlie (Greg Stone), and her infantilised adult son, “Little” Charles (Will O’Mahony). Together they have to deal with the matriarch of the house, the formidable Violet (Pamela Rabe), whose pill-popping truth-bombs drive them all to the edge. All the while Johnna (Bee Cruse), a young Cheyenne woman hired to help around the house, watches.

Pamela Rabe is rightly drawing rave reviews for her bitter/funny/tragic Violet. She’s a tough survivor with an acid tongue and a sharp mind, fueled by her addiction to painkillers. The kind of character you love to loathe. Rabe doesn’t just sink her teeth into the role, she rips open its throat and wears its skin like a cloak. Violet is awful… but rarely is she categorically wrong. Like all the best “villains” her motivation is understandable if often deplorable. Imagine Martha from Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virgina Woolf after George has passed away and you’ll get close to Violet’s core.

However the real superstar performance comes from Tamsin Carroll as the oldest daughter Barbara. Carroll is simply magnificent as a middle-aged woman cracking under the familial pressure coming from all sides. Her performance is seamless and deeply empathetic, so much so it grounds the play, letting the other actors push things broader for laughs. As the foil to Violet, Barbara cuts through the fear and rage with weary clarity. On a stage full of rich, lived-in performances from each and every actor, Carroll shines as its heart.

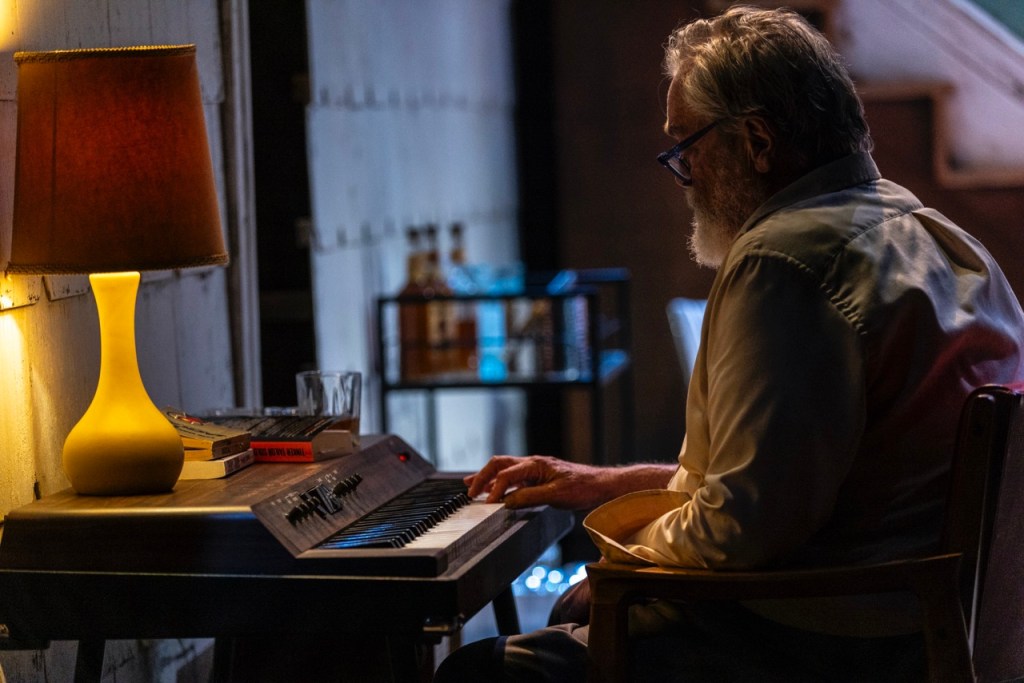

Eamon Flack has directed the show with an understated elegance. After wowing audiences with his showmanship in great productions of Holding The Man and The Master & Margarita etc, this time Flack’s hand is light. Drawing out masterful performances (and creating moments of physical comedy that seem to come out of nowhere), Flack lets the text rise to the fore. He gently turns John Howard’s Bev (who only appears in the first act) into a haunting, melancholy presence that lingers for the whole play.

Set Designer Bob Cousins’ apparently sparse set is also deceptively subtle. The wide open space of the stage stands like the sun-bleached Great Plains, surrounded by elements of a house torn apart and reassembled, with windows and doors out of place. Morgan Moroney’s lighting gives it texture and an essential blast of heat.

Tracy Letts is a visceral writer. He creates a pungent, stifling air with his characters that is intoxicating, like a modern day Tennessee Williams. With August: Osage County he weaves three or four play’s worth of drama into one rich tapestry of dysfunction with a paradoxical lightness of touch that reminds you what good writing, really good writing, can achieve.

Letts never takes the easy way out, by writing characters that are mere cyphers or punchlines (okay, maybe Rohan Nichol’s Steve is a bit one dimensional on the page). Each member of the Weston family has a unique, broken interiority that drives them. They’ve each been damaged by the generation before them and are just trying to do their wounded best. Letts doesn’t judge his characters, he lets them roam free and sees where they will collide.

Lines like “Why were they ‘the Greatest Generation?’ Because they were poor and hated Nazis? Who doesn’t . . . hate Nazis” hit sadly differently as we head toward Tr*mp 2.0, but Letts text still cuts sharp with its indictment of America (Weston = Western), and how we often replicate patterns of abuse to become the things we despise.

“Thank God we can’t tell the future. We’d never get out of bed.” Amen.

Leave a comment