Written by John Patrick Shanley. NicNac Productions. The Old Fitz Theatre. 13 Jan – 1 Feb, 2026.

Two fucked up people trying to find the light collide in John Patrick Shanley’s highly combustible 1983 two-hander, Danny & the Deep Blue Sea. There’s shouting. There’s punching. There’s sex. There’s a little bit of choking. And there’s a lot more shouting again.

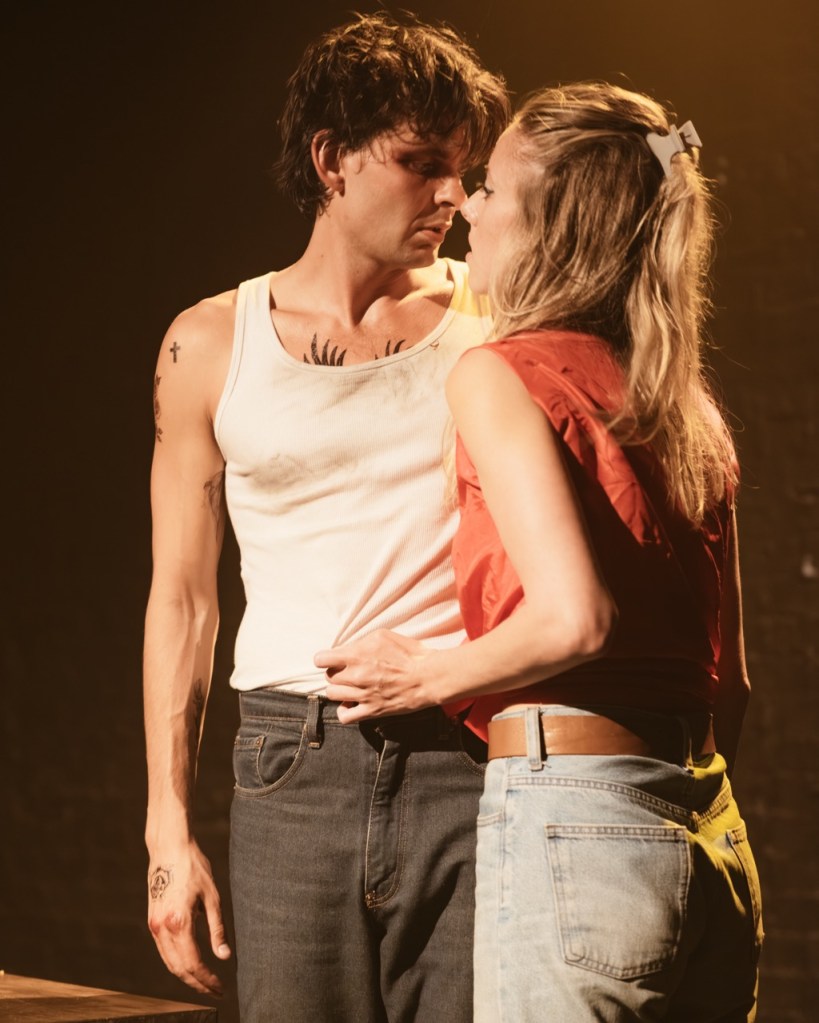

Two Catholics walk into a bar… Danny (JK Kazzi), knuckles bloodied and sporting a black eye, says he wants to be left alone. But over a few pretzels and some beer, he starts talking to Roberta (Jacqui Purvis). Danny has no hope, convinced he may have killed a man in a street fight. Roberta is filled with self-loathing and searching for distraction, perhaps absolution. They’re two people with broken pasts, struggling with the simultaneous urges of fight and flight. But maybe they can help sort each other’s shit out.

Danny & the Deep Blue Sea hails from a wave of late-70s/early-80s Off-Broadway theatre that rediscovered “grit” and aimed squarely for realism. In fact, 1983 was a real high point for fragile masculinity on stage, with David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross and Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love both debuting that year.

These characters sit at a messy inflection point in society, suffering through the early years of the first Reagan administration. They lack the language to describe their pain, or the insight to see any solutions. This is masculinity battered by economic decline and the humiliation of the Vietnam War — men no longer able to see themselves as breadwinners or protectors.

The play’s view on femininity is no gentler: a dark reflection of motherhood, the desire to nurture, and the uneasy aftermath of the sexual revolution. Roberta is a woman who can’t quite step fully into the world being created.

It’s a juicy script for performers eager to show their range, with two manic characters ricocheting from rage and fear to joy, lust, and hope, then back again. At times the scenes feel like a series of audition-ready monologues strung together. Still, the script is well paced — a lovely piece of writing that carries the audience on a compelling journey from beginning to end.

Nigel Turner-Carroll’s new production at the Old Fitz leans hard into the theatre’s inherent dankness. This is a grubby, visceral show that lets the performers rage against the black walls. It’s occasionally overwrought, with hair-trigger emotions leaping from zero to 100 in the blink of an eye, and they don’t always feel earned. And this isn’t really a criticism at all, but I was expecting something to come from the set up of what I will only describe as “Chekhov’s used condom” but I’m also kinda glad there wasn’t.

Jacqui Purvis, probably best known for her stints on Neighbours and Home & Away, sets out to prove her range here — and succeeds. Her Roberta is a festering mix of Catholic guilt and hard-won independence, her inner child sneaking out in flashes before retreating behind a gruff exterior.

Similarly, JK Kazzi gets to emote to the rafters as the erratic and possibly dangerous Danny. There’s a wounded boyishness to his violent tantrums, and a wide-eyed innocence to his yearning for a future he can’t yet imagine.

There are moments when the show’s subtext is written too large in the performances, which may be cathartic, but flattens the scripts latter revelations. These lapses are forgivable with a script this strong. The accents, though… well, you do settle into them, even if it took me half a dozen lines to realise we were in the Bronx and not a pub in Ireland.

Don’t let the opening scene put you off. It’s when Roberta and Danny retreat to the bedroom and begin an emotional strip-tease — slowly opening up to each other — that the show finds its rhythm. This is where the play’s contemporary resonance shines. In isolation, we become bitter and twisted (thank God these characters didn’t have access to social media in 1983), but maybe a little human connection can still show us the way out.

Shanley would go on to win the Pulitzer and Tony Awards for Doubt: A Parable in 2005, using Catholicism to explore even murkier territory (returning to STC later this year BTW – book now). It’s almost frightening how these two plays, written decades apart, tap into distinctly modern anxieties. Danny & the Deep Blue Sea is a crisis of masculinity; Doubt examines the dangers of flawed moral certainty — something that feels uncomfortably resonant in an era of conspiracy theories, religious extremism, and science denial. Maybe it’s time we started re-examining John Patrick Shanley’s work a little more closely.

Leave a comment