-

Welcome to Cultural Binge

The rating system is simple:

★★★★★ – Terrific, world-standard. Don’t miss.

★★★★ – Great, definitely worth seeing.

★★★ – Good. Perfectly entertaining. Recommended. Individual mileage may vary.

★★ – Fine. Flawed and not really recommended, but you may find something to appreciate in it.

★ – Bad (& possibly offensive).

See more reviews over at The Queer Review.

Instagram: @culturalbinge

Substack: culturalbinge.substack.com

Email: chad at culturalbinge.com

-

Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Sydney Theatre Co) ★★★★★

Written by Edward Albee. GWB Entertainment & Andrew Henry Presents the Red Stitch Actors’ Theatre production. Sydney Theatre Company. Roslyn Packer Theatre. 7 Nov – 14 Dec, 2025.

It’s back — the most caustic of all domestic comedies. Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf returns to Sydney with its jagged wit and diabolically broken relationships, brought to the stage by real-life married couple Kat Stewart and David Whiteley.

George (Whiteley) and Martha (Stewart) return home from a faculty party filled with minor complaints. You were too loud. You were too quiet. You weren’t funny. They settle into their tired, drunken bickering routine as George makes Martha a nightcap. But it won’t be a nightcap. Martha has invited a nice young couple they met – Nick (Harvey Zielinski) and Honey (Emily Goddard) – over to keep the party going. Why? Does she just want to humiliate George further? Or is there something more to the games they’re both playing?

Kat Stewart and David Whiteley. Photo: Prudence Upton. I’ll lay my cards on the table early and say that I think Albee’s script is near perfect. It’s a finely tuned machine of subtext, competing motivations, and carefully dropped hints. Yes, the three-hour-plus running time is intimidating. But you’d be hard-pressed to find a single line you’d want to cut. The emotional fever builds carefully over the course of the play, and it would break the rhythm to tinker with Albee’s work. More than sixty years on, it remains a modern masterpiece.

If Albee’s text is a masterclass in structure, his characters are a study in complex, competing motivations and emotional drives. George and Martha are the culmination of decades of slights, frustrations, and dead dreams – middle-aged people who feel too much and can only numb themselves with liquor.

Their world is a sick microcosm of insular jokes and stories only they truly understand. Like an online conspiracy theorist cut off from regular society, they’re losing touch with the real world and retreating into their dysfunctional private hell. You know they’ve had this exact fight before, yet there’s some strange comfort in the repetition – they understand one another completely and that is its own sort of intimacy. It’s only when George changes the game that the true horror settles in.

Kat Stewart. Photo: Prudence Upton. Kat Stewart is invigorating as the academic’s housewife clawing at the walls of her middle-class existence. She brings a feline grace and simmering rage to Martha as she stalks the stage – the world is ignoring her but she is demanding its attention.

While Stewart has rightly been highly praised, I found myself drawn more to Whiteley’s viciously professorial and quick-witted performance. His George is an example of masterfully pitched tone. There’s a menace to his delivery – a sense that George is playing multiple games at once – but that cerebral element never outweighs the emotional drive, the pain, that pushes him forward. Watching these two together is the stuff theatrical dreams are made of. This is gold.

Harvey Zielinski, Emily Goddard and David Whiteley. Photo: Prudence Upton. As the younger academic couple, Nick and Honey, Zielinski and Goddard at first seem miscast – neither fitting the physical descriptions given in the script. But their performances quickly dispel any doubts, especially Goddard, who has the hardest role to balance as a more traditionally comedic figure. Under Sarah Goodes’ direction, she lands her moments without breaking the tone.

All of this comes together under Goodes’ steady hand. She has doubled down on the emotional horror of the story, adding short, ethereal interludes that strengthen the ongoing mystery surrounding George and Martha’s “kid”. As the audience is left to guess how much of what they’re saying is truth and how much is bitter fiction, these moments tease us further.

Harvey Zielinski, David Whiteley, Emily Goddard and Kat Stewart. Photo: Prudence Upton. Harriet Oxley’s design is both spacious and stifling, placing George and Martha’s bar centre stage – there’s no forgetting their lives revolve around alcohol. There are beautiful subtleties in Matt Scott’s lighting and in Grace Ferguson and Ethan Hunter’s sound design (even if one cue felt slightly overused).

This production has grown from Melbourne’s 80-seat Red Stitch Actors Theatre, where it debuted in 2023, to the expanded, full-scale version we see today. These actors have had time to settle into their roles and live with these complex characters – and it shows. The production has already received near-universal acclaim, and it’s clear to see why. Unlike the 2022 production staged at the Sydney Opera House (which I missed, but multiple sources say was a bit of a drag), this version rises to the challenge of the text.

Harvey Zielinski, David Whiteley, Emily Goddard and Kat Stewart. Photo: Prudence Upton. Make no mistake: this is a heavy night at the theatre. As funny as it is watching two people tear each other apart with wit and venom, it’s also a journey into alcoholism and emotional abuse – and, strangely, at the end of the day, a twisted love story. At three hours twenty minutes, including two short intervals (you’ll be racing to either use the loo or get to the bar – good luck doing both), it makes for an intense evening, especially on a school night. But, for my money, it doesn’t get much better than this.

-

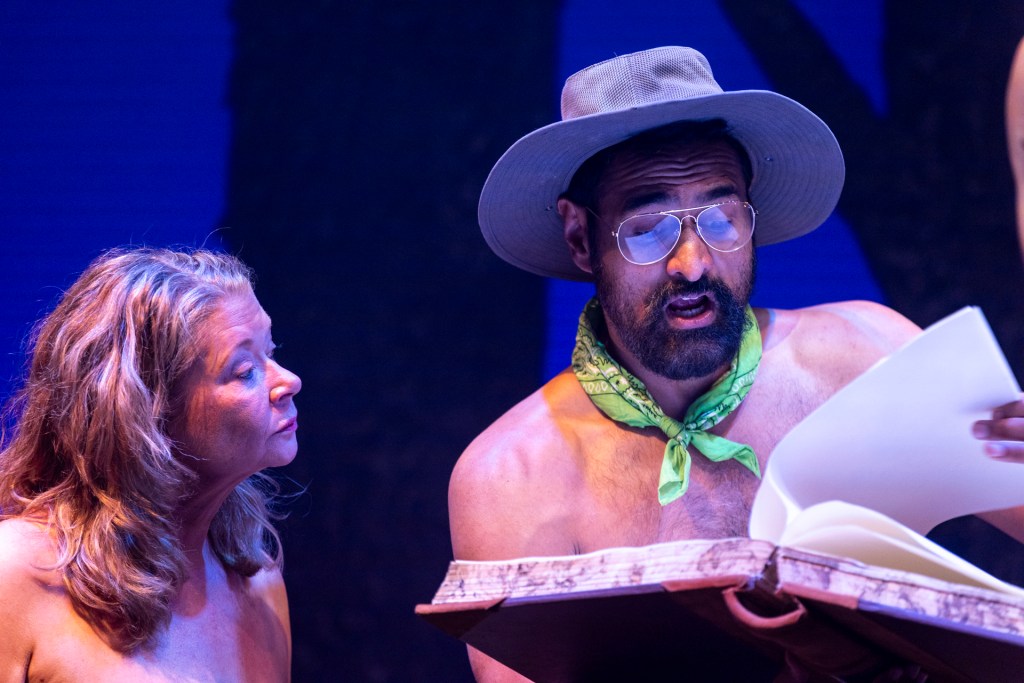

Atlantis (KXT on Broadway) ★★★

Written by Paul Gilchrist. subtlenuance, in association with bAKEHOUSE Theatre Company. KXT Vault. KXT on Broadway. 8-17 Nov, 2025.

KXT on Broadway christens its studio space, the KXT Vault, with a new staging of Paul Gilchrist’s short play, Atlantis. It’s an intriguing choice to open an equally interesting new intimate venue.

Sarah (Veronica Clavijo) and Tom (Jimmy Hazelwood) are on the run. Fleeing Sydney on foot, they’ve hitched rides as far as they could on their way to Byron Bay to see if Sarah’s aunty Zelda (Sylvia Marie) can put them up until things blow over. To earn their keep, they start working in her spiritualist store, hocking crystals and dreamcatchers to the gullible. While they secretly mock the clientele, they start to wonder how different, really, is Zelda’s past life as an Atlantean princess from Tom’s as an inept drug dealer, or Sarah’s as a struggling actress? It’s all in the stories we tell ourselves to make sense of the world.

Veronica Clavijo & Jimmy Hazelwood & Sylvia Marie. Photo: Syl Marie Photography. Written and directed by Gilchrist, this pop-up production makes use of the Vault’s enforced intimacy with numerous fourth-wall-breaking asides that heighten our awareness that this is a story about stories, told by storytellers. Naturalism is not the name of the game here. The heightened language demands your attention, accented with moments of humour.

This is a cerebral affair full of wry observations about life – you can feel the authorial voice speaking through the characters. Between the witty commentary on contemporary society it asks us to consider which stories are worse – the cheeky half-truths and lies Tom tells Sarah, or the kooky delusions Zelda tells herself? One does more harm than the other.

Veronica Clavijo & Jimmy Hazelwood. Photo: Syl Marie Photography. The Vault itself is a simple space, seating about 30 people in two rows, facing a corner. The stage area is given an ethereal quality thanks to tasteful lighting & simple design elements — fairy lights, birdcages, and the occasional wind chime. Washed in a purple glow, things feel otherworldly. The abstraction accentuates the actors, though there is a slightly awkwardness in their performances as they wrangle the dense dialogue that detracts from the emotion.

Almost ten years on from the play’s debut (at the old KXT, as part of the Sydney Fringe 2016), this Atlantis has risen again. It’s a solid start of KXT’s Underground programming – a small scale piece that will get your mind working.

-

So Young (Old Fitz) ★★★★

Written by Douglas Maxwell. Australian Premiere. Outhouse Theatre Co. Old Fitz Theatre. 7-22 Nov, 2025.

“Remember the time…?” – three friends getting together to reminisce becomes a passive-aggressive battle in the darkly funny Scottish domestic comedy So Young. The stories that bind friendships run deep – but are they stopping life from moving forward?

Jeremy Waters, Ainslie McGlynn, Aisha Aidara & Henry Nixon. Photo: Richard Farland. Middle-aged couple Liane (Ainslie McGlynn) and Davie (Jeremy Waters) are invited to dinner by their recently widowed friend Milo (Henry Nixon). All three are still grieving the loss of Helen – Milo’s wife of twenty years and Liane’s best friend. When Milo suddenly introduces them to his new twenty-year-old girlfriend Greta (Aisha Aidara), Liane and Davie do their best to stay civil, but they can only bottle up their outrage and confusion for so long.

Outhouse Theatre Co have always excelled at finding strong writing to bring to the stage, and So Young is no exception. Though conceptually lighter than previous works like A Case for the Existence of God, Heroes of the Fourth Turning or Consent, So Young is an exploration of the heart, not the mind, that gives the cast plenty to chew on.

Jeremy Waters & Ainslie McGlynn. Photo: Richard Farland. McGlynn and Waters bring an easy familiarity to the marriage, full of shorthand and comfortable jests. Their chemistry with Nixon, playing their old school friend Milo, has a natural warmth. Even in their forties, there’s a youthful camaraderie between Davie and Milo that speaks to shared history. Their current frustrations rest on decades-old grievances and familiar patterns of behaviour.

Both Liane and Milo are consumed by grief for Helen, who died alone in hospital during the Covid pandemic. The unresolved nature of that loss seeps into their lives in different ways. Liane is angry and confused, her resentments souring her relationships. Milo is lonely but determined to move forward, refusing to be swallowed by sorrow.

Henry Nixon & Aisha Aidara. Photo: Richard Farland. As the outsider, Aidara’s Greta feels distinctly separate from the others. Playwright Douglas Maxwell goes to great lengths to present her as an equal despite her youth which risks turning her into an idealised woman, rather than a real character. His determination to sidestep older-younger romance clichés sometimes tips the balance – the relationship risks being defined more by what it isn’t than by what it is. Thankfully Aidara’s layered performance fills in the gaps (her reactions are beautifully delivered, even when she is not the focus of the moment).

The success of Maxwell’s script lies not in reinventing a familiar tale – the older man’s younger girlfriend provoking amusement and disgust – but in filling each moment with well-observed detail and sharp dialogue. It’s a smart, grown-up piece that trusts its audience. Every line slots into place like a puzzle piece, revealing character bit by bit. Maxwell deftly avoids inserting references to Covid-era UK politics (“Partygate”, vaccine denial, the image of Queen Elizabeth sitting alone at Prince Philip’s funeral), keeping the focus personal.

Henry Nixon, Ainslie McGlynn, Aisha Aidara & Jeremy Waters. Photo: Richard Farland. Director Sam O’Sullivan makes deft use of the Old Fitz’s intimate space, complemented by Kate Beere’s rich set design. Aron Murray’s lighting is especially adept at smoothing scene transitions and shifting location with simple elegance. O’Sullivan draws an appealing naturalism from his performers – despite their slightly heightened Scottish accents – grounding the play in emotional truth.

So Young may not be the meatiest of dramas, but it’s far from empty comedic calories. Outhouse Theatre Co have doubled down on works that put the laughs front and centre this year, with both So Young and the excellent Eureka Day at the Seymour from earlier this year being crowd-pleasers without sacrificing literary or intellectual merit. There’s plenty to engage both brain and heart and I’m all here for it.

-

The Lovers (Theatre Royal) ★★★★½

Book, music and lyrics by Laura Murphy, based on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Shake & Stir Theatre Co. Theatre Royal Sydney. 31 Oct – 15 Nov, 2025.

Three years after its debut at the Sydney Opera House, Laura Murphy’s musical The Lovers is back with so many giant video screens you’d be forgiven for thinking Kip Williams had come back to town. Bigger, louder and flashier, this version of The Lovers rivals & Juliet for the Pop Shakespeare crown.

Natalie Abbot & Mat Verevis. Photo: Joel Devereux. It’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but not as you know it, as our disco/cowgirl fairy leader Oberon (Stellar Perry) and pouf-ball-headed Puck (Jayme-Lee Hanekom) try to make a couple of Athenian youths fall in love. They just don’t really have a good track record at this romance stuff, and it’s clear to see why.

Loved-up couple Hermia (Loren Hunter) and Lysander (Mat Verevis) have run away so they can get married. But Hermia is being pursued by Demetrius (Jason Arrow), the guy she’s been promised to. Meanwhile, Demetrius is being stalked by Hermia’s best friend, Helena (Natalie Abbott). So if Oberon and Puck can just get Demetrius to fall for Helena, then everyone’s problems are solved, right? Right?

Jason Arrow. Photo: Joel Devereux. First staged in 2022 by Bell Shakespeare, this new production brings fresh staging and a blended cast which sees original cast members Natalie Abbott and Stellar Perry return, joined by Hamilton’s Jason Arrow, Six’s Loren Hunter, Beautiful’s Mat Verevis and more (even the covers are stacked—with Titanique’s Jenni Little and Joseph & the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat’s Nic Van Lits waiting in the wings). It’s a powerhouse team belting Murphy’s hooky tunes—you will walk out singing. Needless to say, the whole show sounds stunning, and everyone gets to stretch their comedy muscles as well.

Jason Arrow & Loren Hunter. Photo: Joel Devereux. Shake & Stir’s Artistic Director Nick Skubij brings an almost sci-fi eye to the musical, with cosmic expanses filling the stage and a lone tree that reminded me of the Hugh Jackman brain-bender The Fountain. Isabel Hudson’s design frames the stage in Elizabethan ruins and makes abundant use of the stage’s triple revolve—that’s right, THREE revolves! Suck it, Les Misérables!

As with the cast, many creatives from the original staging return with a brand-new vision. Trent Suidgeest’s lighting channels stadium pop gigs, and David Bergman’s sound and video design take cues from games and music videos—this is just visually gorgeous work.

Jason Arrow, Loren Hunter, Natalie Abbot & Mat Verevis. Photo: Joel Devereux. Yvette Lee’s choreography carries forward some moves from the original (I instantly recognised the “nay-nay-nay” hand wave) while elevating the comedy of the boys’ rivalry. I don’t know if Lee is also responsible for the confetti-ography, but it was impressive nonetheless. Can you ever have too much confetti? The Lovers is definitely trying to prove the answer is NO!

Musically, The Lovers rocks! Laura Murphy uses the language of pop songs to play with our understanding of Shakespeare and to ground the action for a contemporary audience. And it’s exciting to see the work return on a bigger stage and with a more commercial vision.

Jayme-Lee Hanekom & Stellar Perry. Photo: Joel Devereux. So, if you already saw the 2022 production, should you go see The Lovers again? Yes! I loved Sean Rennie’s pastel-fluid fantasia, but Skubij’s shimmering, sparkly show is a whole new thing. Personally, I just find it exciting to see the same show given two different visual aesthetics in such a short space of time.

Sydney, we’re being spoilt right now, having two terrific Australian musicals on our stages at the same time. So make the most of it—this doesn’t happen very often.

-

Phar Lap: The Electro-Swing Musical (Hayes) ★★★★½

Book, Music & Lyrics by Steven Kramer. World Premiere. Hayes Theatre Company. 17 Oct – 22 Nov 2025.

After strong word of mouth from workshops and readings, Phar Lap: The Electro-Swing Musical has galloped onto the stage — and it lives up to the hype. Steven Kramer delivers a remarkable trifecta: great music, sharp lyrics, and an outrageously bonkers book to match. This show has an abnormally big heart and an even bigger funny bone.

Harry Telford (Justin Smith), a horse trainer on his last legs, convinces businessman David Davis (Nat Jobe) to take a punt on a horse he’s found in New Zealand. It has a promising bloodline — a descendant of winners. But when the sweet little Phar Lap (Joel Granger) arrives with a thick Kiwi accent, he has no competitive drive — he’d rather be doing dressage. Unimpressed, Harry has to find a way to turn this zero into a national hero to save his own hide.

Lincoln Elliot, Shay Debney, Manon Gunderson Briggs, Nat Jobe & Amy Hack. Photo: John McCrae. Plot-wise, it sounds simple enough, but Phar Lap shines in the storytelling finesse Kramer and director Sheridan Harbridge bring to proceedings. The book is a cavalcade of jokes — from Phar Lap’s training partners being named One-One and Two-Two (“One-One won one and Two-Two won one too”) to the hyper-fast commentary on capitalism from the Race Caller (Manon Gunderson-Briggs — her performance is the glue that holds the show together). Kramer has made sure the script is tight and jam-packed. Yet it’s not just jokes and tunes — he grounds us in the historical events of the time, showing how Phar Lap’s underdog success became an inspiration for a nation suffering through the Great Depression (but, you know, he’s made it funny).

Lincoln Elliot & Joel Granger. Photo: John McCrae. Beyond the writing, the performances match the show’s wild energy. Each character is transformed into a hilarious, larger-than-life caricature thanks to impeccable casting and clear direction. Phar Lap’s older half-brother Nightmarch (Lincoln Elliott) is a braggadocious Kiwi bro, while Shay Debney is a scene-stealer as jockey Jim Pike — a leather daddy ready to ride Phar Lap all night long. Amy Hack shines as both the mysteriously accented Madame X and in a small but memorable turn as a “horse girl” fan. But it’s all anchored by Joel Granger’s wide-eyed, innocent Phar Lap. His cheerful, do-good demeanour is infectious, with Granger bringing a childlike Thomas the Tank Engine energy to the role. Even Phar Lap’s darker or stranger moments (like his oddly sexual bonding with Jim Pike, or his growing addiction to sugar cubes) have a gleeful silliness to them.

Kramer’s score is as sharp as his script. Long established as a go-to musical director, he brings skill and depth of musical knowledge to a score that’s high-energy, smart, and littered with gags — a mash-up of Thoroughly Modern Millie, The Great Gatsby (both Baz Luhrmann’s film soundtrack and the current Broadway show), and the tone of Operation: Mincemeat. There’s palpable passion running through this music — give me a cast recording ASAP, please.

That same inventiveness carries through every element of the production. Mason Browne’s costumes instantly impress, transforming actors into upright horses with long-eared jockey caps and braids — so simple but effective. Ellen Simpson’s choreography plays with all the hallmarks of the era in refreshing ways. Hailey Hunt’s set is surprisingly layered (the stage border referencing Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion is a lovely touch), giving room for Trent Suidgeest’s lighting to inject energy and variety into the space. Similarly, Liam Roche’s sound design elegantly brings the racetrack to life.

There are minor quibbles — like the use of recorded taps for the dancing — but these come down to production cost and are easy to forgive in an indie theatre space. The book occasionally drives its punchlines home a little too hard (it’s okay — we all got the “big heart” reference the first time), yet that’s personal preference. For a premiere production, this show is in outstanding form.

Justin Smith & Joel Granger. Photo: John McCrae. Making successful independent theatre is hard. Making successful independent musical theatre is almost impossible. For every Zombie! The Musical, there’s… well, I won’t name them all, but history is littered with the corpses of unimpressive musicals that should never be seen again. It doesn’t just take talent and songwriting — it takes development and producing skill to bring a show like this to the stage. Thankfully, Hayes have done it again, birthing another new Australian musical that feels completely race-ready. The story may be local, but the themes and humour have universal appeal. All Phar Lap needs now is a few more investors and a big enough stage to really stretch its legs and show everyone what it can do.

-

Naturism (Griffin) ★★★½

Written by Ang Collins. Griffin Theatre Co. Wharf 2 Theatre, Sydney Theatre Company. 25 Oct – 15 Nov 2025.

It’s shirts vs skins as Novocastrian playwright Ang Collins pits generations against one another for her climate-comedy, Naturism. And yes, it’s true, the cast are completely nude — but it’s not just a naked cry for attention, at least not in the way you think it is.

Evangeline (Camila Ponte Alvarez) has fled Melbourne in search of peace from the mental turmoil of her internet-influencer lifestyle. She’s heard about a commune of eco-naturists in the rainforest, and it sounds like the perfect place. There she finds a bunch of Gen X burnouts, including Ray (Glenn Hazeldine), a former CEO turned hippie; Helen (Hannah Waterman), a frustrated middle-class artist; and Sid (Nicholas Brown), a philosopher with a love of routine.

But it isn’t the paradise Evangeline expected. Sid is suspicious of her, Helen is tripping on mushrooms, and there are signs that something is wrong with nature as their commune grows unnaturally hotter. Then an oversized SUV delivers the self-absorbed Gen Z man-child Adam (Fraser Morrison), full of grand plans for this tract of land…

Nicholas Brown, Hannah Waterman, Fraser Morrison, Glenn Hazeldine & Camila Ponte Alvarez. Photo: Brett Boardman. Nudity on stage is nothing new — cynical producers have used it to sell tickets for decades. Bums on stage = bums on seats. And putting bare skin front and centre is nothing new for Griffin either. But nudity on this scale is a bold move nonetheless. Somehow, in an age of “prestige TV” sexposition and “content creators” shilling OnlyFans accounts, seeing this much flesh on stage is still initially confronting but then you just get on with the show.

Hannah Waterman & Nicholas Brown. Photo: Brett Boardman. Naturism opts to go for our funny bones first, and our brains second. This isn’t a preachy soap-box play, it’s a daft comedy with plenty of jiggly bits. I’m generally not one to enjoy overtly “silly” humour, but Collins and director Declan Greene keep the cartoonish aspects grounded in real motivations and human behaviour. Or perhaps it’s the nudity itself that brings an extra layer of… honesty? Either way, I found myself both laughing heartily and cheerfully invested in these characters and their collective climate guilt.

As much as Collins is critiquing climate denialism, she is more critiquing the vanity of performative activism. As one generation struggles to come to terms with the damage they have wrought, another faces the task of actually doing the hard, boring work to clean it all up for the sake of their own future. Much like the wild fire roaring toward them, the climate emergency doesn’t care about politics, good intentions or boarders – and everyone will need to deal with the consequences.

Hannah Waterman. Photo: Brett Boardman. Full praise to this cast, who completely embrace their roles — especially the dynamic and hilarious Hannah Waterman, whose delicious voice and reactions had me in stitches, and Camila Ponte Alvarez, whose manic, shallow Evangeline shone. Their commitment makes the absurdity feel surprisingly sincere.

Naturism is also the most fully staged show I’ve seen in the Wharf 2 space. James Browne has delivered a simple but vibrant set and, paradoxically, some outstanding costumes for the cast. David Bergman’s sound and music ground us in a sense of place, working with Verity Hampson’s dynamic lighting that moves from carefully focused spotlights to a magical dreamscape and a raging bushfire. This Griffin team know how to maximise a small space.

Fraser Morrison & Camila Ponte Alvarez. Photo: Brett Boardman. Once the characters are dragged back down to earth by some harsh realities, Naturism asks us to step away from the noise of modern life and consider the natural world around us. Humans — all of us, regardless of age or status — are an incredibly clever bunch of morons, burning the house down as we live in it. Will some onstage nudity wake us up to reality of our ecological problems? At this stage, it can’t hurt to try.

-

Looking Ahead to Sydney Theatre in 2026: Part Two

Another piece of my break down of the 2026 Sydney theatrical season, this time looking at the musicals coming our way (and some other bits & pieces). It’s over on Substack, where all my non-review writing is now going. Part three, looking at the interstate companies, coming in a few weeks.

-

Fly Girl (Ensemble) ★★★★½

Written by Genevieve Hegney & Catherine Moore. World Premiere. Ensemble Theatre. 17 Oct – 22 Nov, 2026.

With a lightness of touch, Genevieve Hegney and Catherine Moore’s Fly Girl is a colourful slice of triumph over the patriarchy. Based on the true story of Deborah Lawrie’s battle to become Australia’s first female commercial airline pilot, it has all the hallmarks of a feel-good hit of the summer – even if we’re still in spring.

Alex Kirwan & Cleo Meink. Photo: Prudence Upton. Young Deborah Lawrie (Cleo Meink) has inherited her father’s love of aviation. Training since her teenage years, all she wants is to pilot aeroplanes – the bigger, the better. After earning her qualifications and becoming both a schoolteacher and flying instructor, she is still repeatedly rejected for Ansett’s commercial pilot training programme – despite the fact that her own students have successfully applied. But things change in 1977 with the introduction of the Victorian Equal Opportunity Act. When Lawrie files a complaint mere days after her wedding, she has no idea the case will span years as Reg Ansett and his team use every trick in the book to try to crush one woman’s dream to fly.

There’s a real buzz in the Ensemble Theatre pre-show, as a particularly rambunctious audience are clearly in a good mood. This is opening-night energy (despite the fact it’s a few nights after). The tone is pushed further by the pre-show addition of Ansett stewardesses in the aisles, greeting guests as they find their seats. I’ve not seen the Ensemble Theatre this alive in… well, ever!

Catherine Moore, Genevieve Hegney, Emma Palmer, Alex Kirwan and Cleo Meink. Photo: Prudence Upton. And that vibe doesn’t stop. Fly Girl has the energy and optimism of a musical, not a legal drama. Grace Deacon’s set and costumes are an explosion of bright orange. It instantly evokes a sense of joy – and maybe naivety. This is peak 70s. The cast all play up to the campy, comedic tone. Despite the story’s inherent tensions, the mood never dips. We’re here to celebrate Lawrie’s triumphs; the setbacks are like pantomime villains we can boo and hiss at.

Hats off to Hegney and Moore for crafting this outwardly sugary confection of a play, and to director Janine Watson for her excellent sense of timing and tone. Together they mine constant micro-moments of silliness without spoon-feeding the audience – whether it’s the slow pace of dialling a rotary landline or the lack of options in in-flight catering – and there’s a constant undercurrent of reassuring schadenfreude, knowing that Ansett itself will eventually fail. This all combines to let the team have their cake and gleefully smash it into Reg Ansett’s face too.

Cleo Meink, Genevieve Hegney, Emma Palmer & Alex Kirwan. Photo: Prudence Upton. The excellent cast of five (playwrights Genevieve Hegney and Catherine Moore are joined by Emma Palmer, Alex Kirwan and Meink) play dozens of roles, necessitating a succession of increasingly outrageous costume changes. By Act Two, even the pretence of leaving the stage to switch is discarded – their transformation becomes a public ballet during the scene changes. Each new character is stamped quickly and clearly as their own comic creation.

The real beauty of Fly Girl is that it isn’t just froth and one-liners. Hegney and Moore have a knack for slipping the lessons in under the radar, and Watson lands the emotional heart at just the right moment. It’s rare to see a play that has the audience applauding mid-scene, celebrating Lawrie’s every triumph.

Genevieve Hegney, Catherine Moore & Emma Palmer. Photo: Prudence Upton. At times, the script does feel like it’s a screenplay (lots of short scenes, a linear narrative of triumph), and I could see this becoming a fun film – anyone in commissioning listening? – or being expanded into a stage musical. (I’m serious: the emotional highs and lows would work well in song, and we have a good, clear villain in Reg Ansett – the positive shout-out to a prominent media mogul might even make fundraising a bit easier.) What it lacks in bite, it makes up for sheer enjoyment – this is as close to a four quadrant hit as I’ve seen on stage in ages.

As the play ended, it became clear why there was an extra buzz in the air: Deborah Lawrie herself was sitting behind me and joined the cast for the bows. Now in her 70s, she’s still an active pilot and a Member of the Order of Australia (AM). Meanwhile, Ansett Airways was liquidated in 2002 after a financial collapse, returning earlier this year as an “AI-powered travel agency” – which sounds horrific. As George Herbert said, “Living well is the best revenge”!

-

Four Minutes Twelve Seconds (Flight Path) ★★★½

Written by James Fritz. Crying Chair Theatre in association with Secret House. Flight Path Theatre. 22 Oct – 1 Nov, 2025.

The characters in James Fritz’s sexting drama have all the foibles of real people in an unexpected and seemingly impossible situation. It makes for some juicy, compelling drama in Four Minutes Twelve Seconds.

When a sex tape of a teenage couple is leaked online, all hell breaks loose as Di (Emma Dalton) and David (James Smithers) must protect their son Jack from allegations of abuse and revenge porn, while also trying to get to the bottom of what really happened. Who leaked the footage? Was it Jack’s mate Nick (Nicholas McGrory)? Why did Jack’s girlfriend Cara (Kira McLennan) suddenly dump him? How much do parents really know about their teenage children?

James Smithers & Emma Dalton. Photo: Phil Erbacher. The play Four Minutes Twelve Seconds is ten years old, and while parts of the tech mentioned feel dated, the human drama is very much contemporary in its impact. Fritz’s dialogue is sharp and layered, giving the performers room to bounce off one another like real conversations. When it works, this play crackles with that addictive theatrical energy.

Fritz makes the interesting choice to remove Jack’s voice from the narrative, he is never seen or heard, merely existing as an pressence in the next room. It places the story firmly in the parents perspective which gives it clarity and relatability. This puts the moral quandary on the shoulders of Jack’s mum, Di, as she wrestles with the thought that maybe her son isn’t the boy she thought he was — and what responsibility she bears to try to make things right. It’s a juicy role with some wonderful twists and turns. While some of the later plot developments don’t quite pass the real-life “sniff test”, they all make clear emotional sense, which earns the play a lot of leeway.

Emma Dalton & James Smithers. Photo: Phil Erbacher. The creative team has placed the emphasis heavily on the performances. A clean, stylish stage (lovely, concise design work by James Smithers, on top of his acting role) makes smart use of the Flight Path space. Lighting by Clare Sheridan accents the great AV design of Kieran Camejo. Director Jane Angharad keeps the patter of the dialogue moving at a fast, naturalistic pace, which elevates the sometimes static staging.

Smithers is excellent in his onstage role as the protective father of Jack. His grasp of the rapid-fire text and character work saves the role from feeling repetitive, despite many of the scenes treading similar territory time and again. Also refreshingly good is Kira McLennan as Cara, Jack’s attractive ex-girlfriend from the wrong side of the tracks. Her aggression-hiding-her-fear dynamic pulls the story out of its middle-class POV and places it in a wider world.

Emma Dalton & Kira McLennan. Photo: Phil Erbacher. As Jack’s devastated mother, Emma Dalton has the bulk of the dialogue and emotional journey. Dalton wisely avoids easy melodrama with a performance that fights between interiority and expression. However, with so much stage time and such a wordy, looping script, it could benefit from a bit more light and shade.

It’s interesting to see Four Minutes Twelve Seconds soon after watching Suzie Miller’s Inter Alia, which covers similar ground — parents floundering in the face of sexual abuse allegations against their sons. It’s fascinating to see how the two plays, written over a decade apart, handle the topic. Inter Alia left me asking “what do you do after the bombshell has dropped?”, which Four Minutes Twelve Seconds tries to tackle. James Fritz’s answers are bold and thought-provoking and will have the parents in the room rattled.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.