-

Welcome to Cultural Binge

The rating system is simple:

★★★★★ – Terrific, world-standard. Don’t miss.

★★★★ – Great, definitely worth seeing.

★★★ – Good. Perfectly entertaining. Recommended. Individual mileage may vary.

★★ – Fine. Flawed and not really recommended, but you may find something to appreciate in it.

★ – Bad (& possibly offensive).

See more reviews over at The Queer Review.

Instagram: @culturalbinge

Substack: culturalbinge.substack.com

Email: chad at culturalbinge.com

-

Looking Ahead to Sydney Theatre in 2026: Part One

I’ve written another installment in my ‘no-one-asked-for-this’ break down of the 2026 Sydney theatrical season. It’s over on Substack, where all my non-review writing is now going. Part two coming in a few weeks.

-

The Edit (Belvoir 25a) ★★★★★

Written by Gabrielle Scawthorn. Unlikely Productions. Legit Theatre Co. Belvoir 25a. 7-26 October, 2025.

Reality TV get its own ‘villain edit’ in The Edit, podcaster and actress Gabrielle Scawthorn’s brilliant drama set in the world of a reality TV relationship show. Spoiler alert: this might be one of the best dramas I’ve seen all year.

Influencer Nia (Iolanthe) wants to find her life partner on the reality dating show ‘Match or Snatch’. She’s been assigned to Field Producer Jess (Matilda Ridgway), who explains how things work and ensures Nia gets where she needs to be on time. Jess is thrilled to discover that beneath Nia’s fantastic body and bubbly personality, Nia is a genuine romantic at heart — she is reality TV gold. Maybe this beautiful Black girl is exactly what Jess needs to break through the racism of reality TV casting. Maybe she can be the one to help this girl win the show. But in a world of image manipulation, who is actually telling the truth?

Iolanthe & Matilda Ridgway. Photo: Robert Catto. Gabrielle Scawthorn (who pulls triple duty as writer, director and costume designer) has produced an incisive work that never gives away its intentions. It’s full of shifting power dynamics that constantly play with the audience’s expectations, delivering surprise after surprise. From the opening scene, we realise neither woman is who she first appears to be. Nia is playing up to the show’s tropes — she’s sexy, romantic and upbeat — but in truth, she’s arrived with a carefully thought-out strategy. Meanwhile, Jess presents herself as a powerless junior newcomer to the show, when in fact she’s worked on it for years and has her eyes on the Executive Producer role. They are both as dangerously ambitious as each other.

Matilda Ridgway. Photo: Robert Catto. Crafted from interviews with former reality TV contestants and producers, it’s clear Scawthorn (who has had her own brush with reality TV in the past) understands the world of reality television and the people in it. There’s a cold, constant awareness that everyone is projecting a version of themselves — everyone is playing to an unseen camera, working their angles, playing the game – even when there are only two people in the room.

The beauty of Scawthorn’s writing is how convincing and genuine both women are. Even at its darkest points, Nia and Jess’s harsh summation of their options carries a clinical, but honest, truth. These women have complex motivations and are placed in complex situations — it’s the stuff great drama is made of.

Iolanthe & Matilda Ridgway. Photo: Robert Catto. As sharp and exhilarating as the script is, the show rests on the shoulders of Iolanthe (Seven Methods of Killing Kylie Jenner, Sistren) as Nia, and Matilda Ridgway (terrific in everything from Bell Shakespeare’s Coriolanus to Belvoir hits like The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and The Master and Margarita) as Jess. These are intelligent, multilayered performances. The intimacy of Belvoir’s Downstairs Theatre means you can really watch each moment unfold. This is the kind of show where the smallest look can get a gasp from the audience.

Iolanthe & Matilda Ridgway. Photo: Robert Catto. And the production elements match the scale of the writing & performances. Scawthorn brings a clean specificity of the costume choices as well that accentuates the drama. The scene & set changes have even been elevated to mini-moments – this is Scawthorn’s vision from top to toe and it’s exhilarating. Ruby Jenkins’ set never lets you forget the reality of the world we’re in. Phoebe Pilcher’s lighting add a harsh, thumping heartbeat to moments. The Edit also makes excellent use of its audio – terrific sound design from Alyx Dennison & Madeleine Picard.

Full disclosure: I’m a reality TV post-producer (that’s my day job), so this is a world I know well. The events of The Edit are incredibly rare — but they are, sadly, based on true stories from around the world. Scawthorn has used the genre’s worst impulses and magnified them to create a heightened drama that is, for me, close to perfect — I can’t recommend this one highly enough.

-

Fekei (Qtopia)

Written by Sarah Carroll. Qtopia Loading Dock Theatre. Oct 8 – 18, 2025.

For many Fiji is a holiday destination for sun, beaches and friendly locals, but for Akanisi (Melissa Applin) it’s the home of her extended family and some tough decisions she has to face. Born in Australia, she suffers the same dislocated ennui of many second generation Aussies – feeling that pull of another island on her heart.

But Akanisi’s return to Fiji this time is fraught as she goes back into the closet for fear of the wrath of her grandmother and her deeply religious views. This doesn’t impress her white, Aussie girlfriend Sam (Natalie Patterson) who gets demoted to “roommate”. But maybe the two lesbians aren’t the only queer people in the household… Akanisi’s cousin Fatiaki (Naisa Lasalosi) does seem to love the musical Wicked quite a lot…

Naisa Lasalosi & Natalie Patterson. Photo: Defne. Fekei trends fairly similar ground to many second-gen immigrant stories, especially those centred on queer characters. The tension between a progressive and open life in Australia is at odds with the more religious and traditional focus on family expectations back home. The specificity of Fijian culture adds colour, but doesn’t stray far from the formula.

Carroll’s script is heartfelt but clearly still working out its own rhythms. At a tight 60 minutes, there is room for more depth and more originality. The drama is perfunctory but the comedy keeps the play alive. Kikki Temple and Naisa Lasalosi both turn out fun, silly performances that play with the audience. Some of the laughs are cheap, but they’re genuine. Temple especially gives Akanisi’s grandmother a loving but steely edge that will not bend – both hilarious and heartbreaking.

Natalie Patterson & Melissa Applin. Photo: Defne. Fekei feels like it’s still figuring out what form it will finally take, and this production at Qtopia is a good place to get it up in front of audiences and see how its landing. Once the script is finessed and handed over a more confident director it will be interesting to see what Fekei’s potential might yield.

-

The Shiralee (Sydney Theatre Co) ★★★★

Adapted by Kate Mulvany. Based on the novel by D’Arcy Niland. Sydney Theatre Company. Sydney Opera House, Drama Theatre. Oct 6 – Nov 29, 2025.

A cast of STC all-stars, and a brilliant STC debut, make The Shiralee a feast for lovers of great performances. As bush poetry transforms into onstage drama, Kate Mulvany’s adaptation of the ’50s Aussie classic hits big with both characters and emotions.

Swagman Macauley (Josh McConville) lives by a simple code: no attachments, no obligations. After leaving a pregnant lover behind in Goulburn, he heads to Sydney and fathers a child with another woman, Marge (Kate Mulvany). But family life doesn’t sit well with him, and he hits the road to earn a living, returning to his family only intermittently.

When he comes back to find his nine-year-old daughter Buster (Ziggy Resnick) drunk and neglected, and Marge in bed with another man he snaps. In a rage, he assaults Marge’s lover, takes Buster, and leaves — hitting the road again, only this time with a child in tow. As he teaches her the way of the outback, she slowly teaches him how to be a father.

Ziggy Resnick & Josh McConville. Photo: Prudence Upton. The heart and soul of this father-daughter story lies in the chemistry between McConville and Resnick, which absolutely beams from the stage. With 2025 eyes, the “parent/child on the road” trope feels familiar — from Lone Wolf & Cub to The Mandalorian and The Last of Us. But The Shiralee predates them all, and the uniquely Australian setting, combined with the tender dynamic between McConville and Resnick, keeps it feeling fresh.

Both McConville and Resnick layer their performances with emotional truth that fills each scene — these are honest portrayals befitting the “Aussie battlers” they embody. It could not have been more perfectly cast. McConville brings a wounded soul to the harsh Macauley, keeping the audience sympathetic without softening his tough exterior. It’s a muscular performance that avoids lazy stereotypes.

Josh McConville & Ziggy Resnick. Photo: Prudence Upton. Resnick turns “being annoying” into Buster’s charming superpower as the precocious child slowly discovers the world anew. Casting an adult to play a pre-teen is a risky move, but Resnick brings an unassuming honesty to the role that plays into a child’s innocent brashness — it’s an endearing STC debut.

Around them, a cast of talented comic actors play things straight to great effect. Stephen Anderson, Paul Capsis, Lucia Mastrantone and Aaron Pedersen modulate a variety of smaller roles to bring light and shade to the story. The laughs come easily, but they’re all laced with the dusty tragedy of lives lived in harsh conditions. Catherine Văn-Davies delights as the tough, independent country beauty Lily, as does Mulvany as the complicated and tormented Marge — both roles hugely benefiting from Mulvany’s adaptation, which refuses to reduce the female characters to mere ciphers.

Catherine Văn-Davies. Photo: Prudence Upton. There are moments of poetry in Mulvany’s text that truly sing and give The Shiralee scale. It also helps smooth over the rougher edges of the time, giving Mulvany room to balance out Macauley’s harsh masculinity with hints of hard-won respect for the Indigenous and queer people around him. In McConville’s hands, these moments feel organic, not merely grafted onto the original narrative.

Ziggy Resnick, Paul Capsis & Josh McConville. Photo: Prudence Upton. However, there’s a dip in the dramatic tension of second act that robs the story of some momentum. The act break’s “cliffhanger” feels abrupt and unearned, as does the second act’s major plot moment. I needed a fraction more foreshadowing or narrative hand-holding to stay onboard with the story — a bit more nuts-and-bolts prose to balance the poetry.

While The Shiralee struggles to build to its final emotional landing, it’s a fighter — full of grit, heart, and soul. With a cast this stacked, and two standout performances from McConville and Resnick, you won’t walk away disappointed.

-

Rent (Sydney Opera House) ★★★★★

Book, music & lyrics by Jonathan Larson. Opera Australia. Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House. 1 Oct – 1 Nov, 2025.

Director Shaun Rennie’s Rent is back, transformed from its earlier 2021 iteration—grown into something larger, stronger, and more deeply grounded. This is Rent done right: a must-see.

This cast is stacked with youthful talent from top to bottom. There is an eagerness in their performances that strives not to just give us the familiar big notes and strut the stage, but to act out each moment with specificity as if it were brand new. They’re giving us the kind of fully rounded characters musicals demand but so rarely receive. The whole experience felt like watching Rent for the first time all over again.

Harry Targett & Kristin Paulse Photo: Neil Bennett. Harry Targett (Dear Evan Hansen) proves himself a leading man, making Roger (a character I’ve always struggled to appreciate) both likeable and believable in his struggles. He’s sullen and withdrawn, yet eager to connect—those two competing drives make him fascinating to watch. His playful sadness turned a character I often find one-note into something far more layered*.

Kristin Paulse (Tina: The Tina Turner Musical) is a killer Mimi—perhaps the first I’ve seen to balance the role’s sexuality and addiction with equal amounts of genuine charm. Mimi and Roger’s horniness over their mutual HIV diagnosis feels almost quaint in an age when HIV can now be rendered undetectable (and therefore untransmittable), and drugs like PrEP help prevent new infections, but there is an emotional truth to their connection.

Henry Rollo & Imani Williams. Photo: Neil Bennett. Henry Rollo (The Rocky Horror Show) may be the first Mark to push the indelible image of Anthony Rapp out of my mind. His sharp diction pays off in huge dividends as he wraps his voice around the lyrics of “La Vie Bohème” and nails every syllable. And I have to carve out space to praise Calista Nelmes’ Maureen. “Over the Moon” is notoriously hard to land without tipping into parody, but she owns the stage from the first beat.

Calista Nelmes. Photo: Pia Johnson. That’s not to ignore the rest of the cast. Jesse Dutlow (& Juliet) brings warmth and joy to Angel, infusing extra life into Googoorewon Knox’s (Hamilton) soulful Collins. Imani Williams (Hadestown) gives Joanne a strong arc—from frustrated, doting girlfriend to confident, sexual equal. And the ensemble is filled with stars in their own right who seize their moments and elevate them. I’m seriously tempted to keep an eye out for days when the alternates take the lead roles as they’re all of such a high caliber.

Much of this success can be traced back to Rennie’s direction. He has clearly lived with this material long enough to find extra nuance in the script and characters. This production excels at the small things that could be easily overlooked. Where the earlier 2021 version was solid but small in scale, this new one has been touring the country through 2024, growing and finessing as it went. It’s a testament to what can happen when creatives have the time and budget to fine-tune their work. In 2021, this creative team was good. In 2025, they are at the top of their game.

Cast of Rent – La Vie Bohème. Photo: Neil Bennett. Luca Dinardo’s choreography shifts seamlessly—subtly guiding characters in quieter moments, then bursting scenes open with dynamic energy —“La Vie Bohème” is a triumph. Dan Barber’s set design makes full use of the Joan Sutherland Theatre space (My only quibble? Could we not stretch to a revolve on stage? Watching the ensemble manually spin Mimi and Roger on tabletops was anxiety-inducing). Paul Jackson’s lighting evokes a rock concert aesthetic while also focusing the action beautifully. Ella Butler’s layered costumes give each character history and status – and Maureen’s “Over The Moon” outfit has to be seen to be believed.

If I had to pick a fault, it would be that the sound occasionally became muddy in the big, full-company numbers with multiple counter-melodies—but that’s really stretching to nitpick.

Jesse Dutlow. Photo: Neil Bennett. I’m no Rent-head, but I’ve had a year full of Jonathan Larson—seeing members of the original Rent cast on stage, catching the Off-Broadway run of The Jonathan Larson Project, and rewatching the film of Tick, Tick… Boom! just because I love it. I even visited the New York Theatre Workshop—the original home of Rent—for the first time this year. And as good as Larson’s other works and works-in-progress were, there’s clearly something special about how layered and complete the vision behind Rent was.

If you’ve not seen Rent (or only experienced the film version) then seeing this production is frankly a non-negotiable – book now! If you saw the 2021 version I’d still say to go see it again because this is on a whole different scale to what you saw before. The joy of this new production lies in its careful balance—reverent, but bursting with exuberance. It’s as if Angel is whispering to us from the wings: “Turn around, girlfriend, and listen to that boy’s song,” one more time.

Cast of Rent. Photo: Neil Bennett. *Okay silly spoilers from here… Can we talk about Roger’s dumb ass reaction in the final scene? His girlfriend is dying and he’s like “hang on a second, can you just listen to this song I’m working on?” Seriously dude! What next? You want her to stop coughing so you can tell her about the Roman Empire?

-

The Talented Mr Ripley (Sydney Theatre Co) ★★★★

Written by Patricia Highsmith. Adapted for the stage by Joanna Murray-Smith. Sydney Theatre Co. Roslyn Packer Theatre. 19 Aug – 28 Sep, 2025.

Be gay, do crimes. Patricia Highsmith’s delectable, social-climbing sociopath Tom Ripley hits the stage in a heady mix of envy, murder, and clothes-swapping — these guys barely have time to put a shirt on before they’re taking it back off again.

Tom Ripley (Will McDonald), an awkward young man scheming and scamming his way through life, is recruited by the unwitting Greenleaf family to find their wayward son, the rich, handsome Richard “Dickie” Greenleaf (Raj Labade), and bring him back to America. When Tom finds Dickie drifting through life in Italy, he is invited into this world of luxury and ease, and Tom finds himself seduced in more ways than one. But when Dickie starts to freeze him out again, the chameleonic grifter decides to replace the spoiled rich kid and live the life he’d only ever dreamed of.

Raj Labade, Will McDonald & Faisal Hamza. Photo: Prudence Upton. There is a distinct youthfulness to this production of Ripley that feels less connected to the well-known screen adaptations (apologies to both Matt Damon and Andrew Scott — neither exactly screamed “mid-twenties” in the role), and more in tune with Alain Delon’s 1960 film version Plein Soleil, or the obviously Ripley-inspired Saltburn. All the lead characters are callow twenty-somethings, consumed by their own sense of self – a brash carelessness that works against them.

Will McDonald delivers a seductively lithe lead performance. This Tom Ripley is always watching, observing, mimicking behaviour to hide in plain sight — as a young gay man in the 1950s, it’s his survival mechanism. This is a study in carefully concealed queerness — a yearning that is suppressed but reveals itself in other ways. As an outsider to mainstream society, he doesn’t feel bound by the rules and morals of others. There’s a sadness, mixed with envy, in Ripley’s outlook that curdles into violent resentment when Greenleaf rejects him.

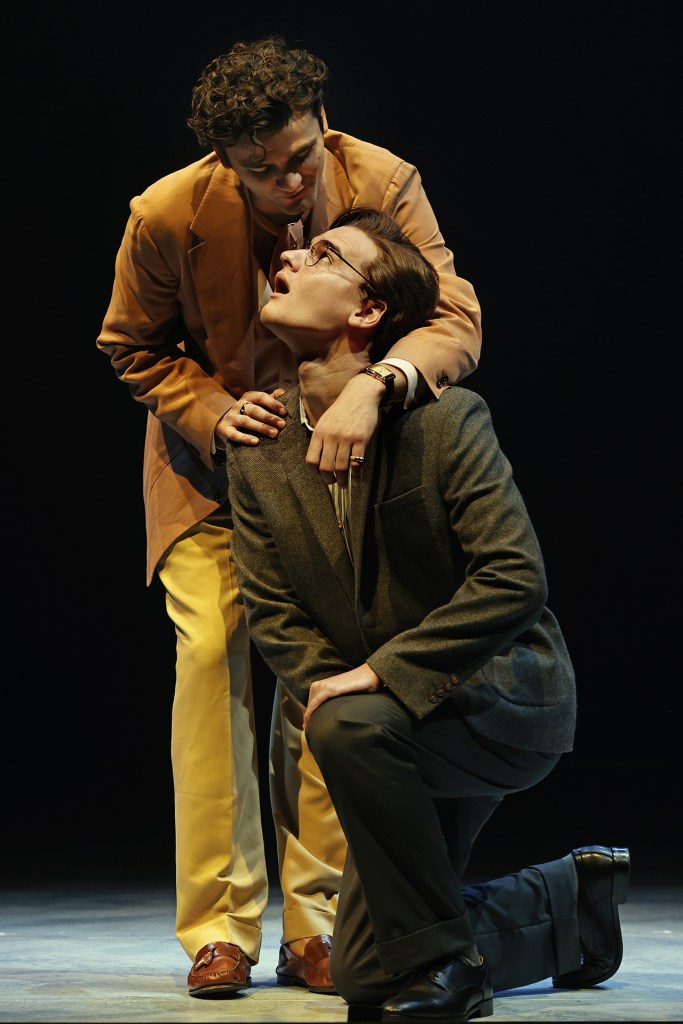

Will McDonald & Raj Labade. Photo: Prudence Upton. Raj Labade’s Dickie is a complete contrast. He is relaxed and entitled, bored of his own privileges and desperately seeking novelty. Both men are indifferent to the people around them, using others purely as tools. As an onstage duo, there’s a crackling energy between McDonald and Labade — the homoerotic thrill of a gay man and a flirty straight man that can never be consummated.

Murray-Smith’s script races through the twists of the novel at a brisk pace. Large sections are narrated by Ripley, giving us quick insights into his thoughts and emotions. It’s expedient, but not always dynamic. However, it does allow for moments of sly comedy, as the audience is privy to Ripley’s uncensored reactions that other characters never see. Once we step outside the core duo, the characters start to feel a little weaker — both Marge (Claude Scott-Mitchell) and Freddie (Faisal Hamza) are less well drawn, often resulting in one-note scenes of vague suspicion.

Photo: Prudence Upton. There’s a distinct visual design to Goodes’ production that strikes a bold note. When it works, it excels — such as in the moment Greenleaf and Ripley go dancing, or during the fateful boating scene — but often the imposing, stark concrete wall dominating the set sits heavily across scenes. Its ever-present threat may be brutalist chic, but for me, it flattened the tone — an expanse of mid-century modernist grey that drained the dynamism and passion from the Italian getaway.

When Sydney Theatre Company announced this show last year, my first reaction was a bemused “huh”. As much as I love the book, the multiple film versions, the Netflix miniseries, and Murray-Smith’s previous examination of Highsmith in Switzerland, I couldn’t immediately see the need for a stage adaptation right now. What could this story say to Sydney in 2025?

Will McDonald & Raj Labade. Photo: Prudence Upton. The answer, it turns out, is… not much. I thought we might be in for some commentary on the technologically induced lack of empathy among young people, or a connection to modern con artists like Anna Sorokin/Anna Delvey. But nope — this is just an entertaining adventure. This is comfort-crime on stage, like watching one of the recent Agatha Christie’s, perfect for the last weeks of winter.

The result is a slick piece of theatre that orbits a magnetic lead performance from Will McDonald. My over-familiarity with the source material may have dulled the plot’s thrills, but the performances kept me completely engaged from beginning to end.

Raj Labade & Will McDonald. Photo: Prudence Upton. -

Kimberly Akimbo (MTC) ★★★★

Book & lyrics by David Lindsay-Abaire. Music by Jeanine Tesori. Based on the play by David Lindsay-Abaire. Melbourne Theatre Company & State Theatre Company South Australia. Arts Centre Melbourne Playhouse. 26 Jul – 30 Aug, 2025.

Five-time Tony Award-winning musical Kimberly Akimbo is quirky, charming, and completely original. We all need to give director Mitchell Butel the full “Paddington hard stare” until he programmes it at STC.

Kimberly Levaco (Marina Prior) is on the verge of turning 16. Born with a rare genetic disorder that causes her to age four to five times faster than normal, she looks like a middle-aged woman but has the mind and heart of a teenager. Settling into a new school, she meets nerdy boy Seth (Darcy Wain), whose blunt lack of social graces and awkward charm get past her defensive nature. Meanwhile, her less-than-honest Aunt Debra (Casey Donovan) has cooked up a get-rich-quick scheme that hinges on Kimberly’s unique condition.

Nathan O’Keefe, Marina Prior, Casey Donovan & Christie Whelan Browne. Photo: Sam Roberts. The adults in Kimberly’s world are… well, calling them “a mess” is being generous. They’re callous and cruel in their own ways. Narcissistic mum Pattie (Christie Whelan Browne) is pregnant again and recovering from surgery on both hands. Her dad Buddy (Nathan O’Keefe) is a drunk with a grudge against his sister-in-law Debra. Kimberly is not only physically ageing too fast — she’s had to grow up emotionally to take care of the useless adults who should be looking after her. And in the background, always, is the reminder that people with her condition rarely live beyond 16.

Which all sounds depressing as hell, but like the best comedies, there’s desperate humour baked into the chaos that keeps Kimberly Akimbo grounded in real emotion. Debra’s scheme is ridiculous, but the stakes are real for Kimberly, who wants the money so she can have an adventure before her time runs out. David Lindsay-Abaire’s book gives us slightly exaggerated but vividly drawn characters — more than you’d expect from most musicals.

Nathan O’Keefe & Marina Prior. Photo: Sam Roberts. And while the subject matter can be heavy, the show handles it with a remarkable lightness of touch. Tesori fans hoping for the weight of Caroline, Or Change or Fun Home might be surprised by the levity and silliness here — as I was when I first saw the show back in 2021. This is a gentler piece, leaning into the zany, 90s indie-cinema / Sundance crowd-pleaser vibe rather than tortured emotion. It’s not a frivolous show, but it doesn’t cut quite as deep as Tesori’s heavier works.

Marina Prior is instantly winning as the young Kimberly. She captures Kimberly’s quiet heartbreaks and fears with subtlety worth watching closely. Christie Whelan Browne and Nathan O’Keefe turn two highly unlikeable parents into layered, interesting people — not redeemable, but understandable in their desperation. Casey Donovan sings the pants off her numbers, but I’ll be honest — her comedy felt too broad compared to the rest of the cast and occasionally threatened to throw off the balance of a scene.

Marina Prior. Photo: Sam Roberts. The real standout is newcomer Darcy Wain as Seth, Kimberly’s new friend and possible first love. His joyful, blissfully unaware performance radiates innocence and honesty, which lifts Prior’s Kimberly and throws her family’s toxicity into sharper relief. His own pain draws them together, and his openness gives her a new lease on life. Wain’s vocals are bright and his performance layered.

He’s joined by a quartet of fellow students — Marty Alix, Allycia Angeles, Alana Iannace and Jacob Rosario — caught in an unrequited love-quadrangle (love-rectangle? love-polygon?). They don’t just keep the energy up; they nearly steal the show. As choruses go, they’re a dynamic, funny bunch — I’d happily watch a spin-off from their perspective.

Full Ensemble of Kimberly Akimbo. Photo: Sam Roberts. Director Mitchell Butel again proves his deep understanding of musical theatre, delivering both spectacle and heart. Jonathan Oxlade’s set, full of childlike geometric shapes, highlights Kimberly’s innocence and naivety. The stage crew deserve their own standing ovation for wrangling the occasionally unwieldy set pieces. Ailsa Paterson’s costumes evoke the 90s without veering into cliché. And kudos to whoever picked the 90s pop bangers for the pre-show playlist — inspired.

Kimberly Akimbo hits that sweet spot between crowd-pleasing & thoughtful without being bland or patronising. It’s commercial with an art-house edge. The score doesn’t feature big Broadway belters you’ll be humming on the train home, but it’s filled with sharp, ear-catching phrases that stick with you long after the final bow.

So if you’re a musical theatre fan, don’t wait. Get to Melbourne before Kimberly Akimbo disappears — there’s no telling if Sydney will get its chance.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.